Transaction

Short Description

A transaction is an exchange of goods, services, funds, or data between some parties. These parties are called the participants of the transaction. A typical business transaction consists of three phases. In the first phase, a transaction agreement is negotiated between the participants. That phase ends when either participant quits the negotiation, or all participants commit to the transaction, which basically is a promise to the other participants that it will keep up its end of the transaction agreement. In the second phase, the participants work to fulfill their promise. That phase ends when they deliver the results, and inform their peers of that they're done. In the final phase, participants check whether or not they have received what was promised, and that it conforms the criteria in the transaction agreement. This may lead to some discussion and possible rectifications. The final phase ends either when one of the participants escalates (e.g. goes to court), or all results are accepted. This way of looking at business transactions has been described extensively in the DEMO transaction model.

It is common for transactions to be governed by (the legal system(s) of) at least one jurisdiction, because they can contain relevant rules of various kinds, e.g. in the areas of

- escalation - i.e. what can be done if a transaction goes sour;

- privacy - e.g. whether or not the GDPR or related legislation applies;

- representation - e.g. rules about how old one must be in order to be entitled to do something, rules on how one may represent an organization or a person, guardianships, etc. and others.

Additional content is needed here.

Explanation required about 'commitment decision' (i.e. 'promise' decisions in DEMO).

High Level Example

In its simplest form, this may be envisaged as one party (requestor) that requests another party (provider) to provide some product, e.g. a parking permit, by using his web-browser to navigate to the web-server of the provider (e.g. his municipality) where he is prompted to fill in a form to provide the details of his request (such as name, address, plate number, etc.). When the form is submitted, the provider decides whether or not to service the request (provide the parking permit) based on the data in the form, and take actions accordingly.

In order for this to work, the provider must design the form such that when a requestor submits a completed form, it can actually decide whether or not to service the request. This has two parts: first, the provider must specify the argument (i.e. the way of reasoning) that it uses to reach this decision - i.e. provide the parking permit. Doing so implicitly specifies the kinds of data that the form will ask for. Secondly, the provider must decide for each of the data it receives, whether or not it is valid to be used in that argument - the process of deciding this is called 'validation'. Common criteria that help to make this distinction include whether or not the data is presented in the expected format, whether or not it is true (not so easy), whether it is not outdated, or whether or not it satisfies validation rules (in the example, the municipality may require that the specified license plate belongs to a car owned by the person that requests the permit). Validation is important, because reasoning with invalid data may result in wrong conclusions and cause damage.

Perhaps the most important contribution that the eSSIF-Lab project aims to make, is to create a ubiquitously used infrastructure for designing, filling in, and validating forms (not just web-forms, but also for 'forms' - e.g. JSON objects - in API requests). The benefits this will bring are enormous, but outside the scope of this document to list.

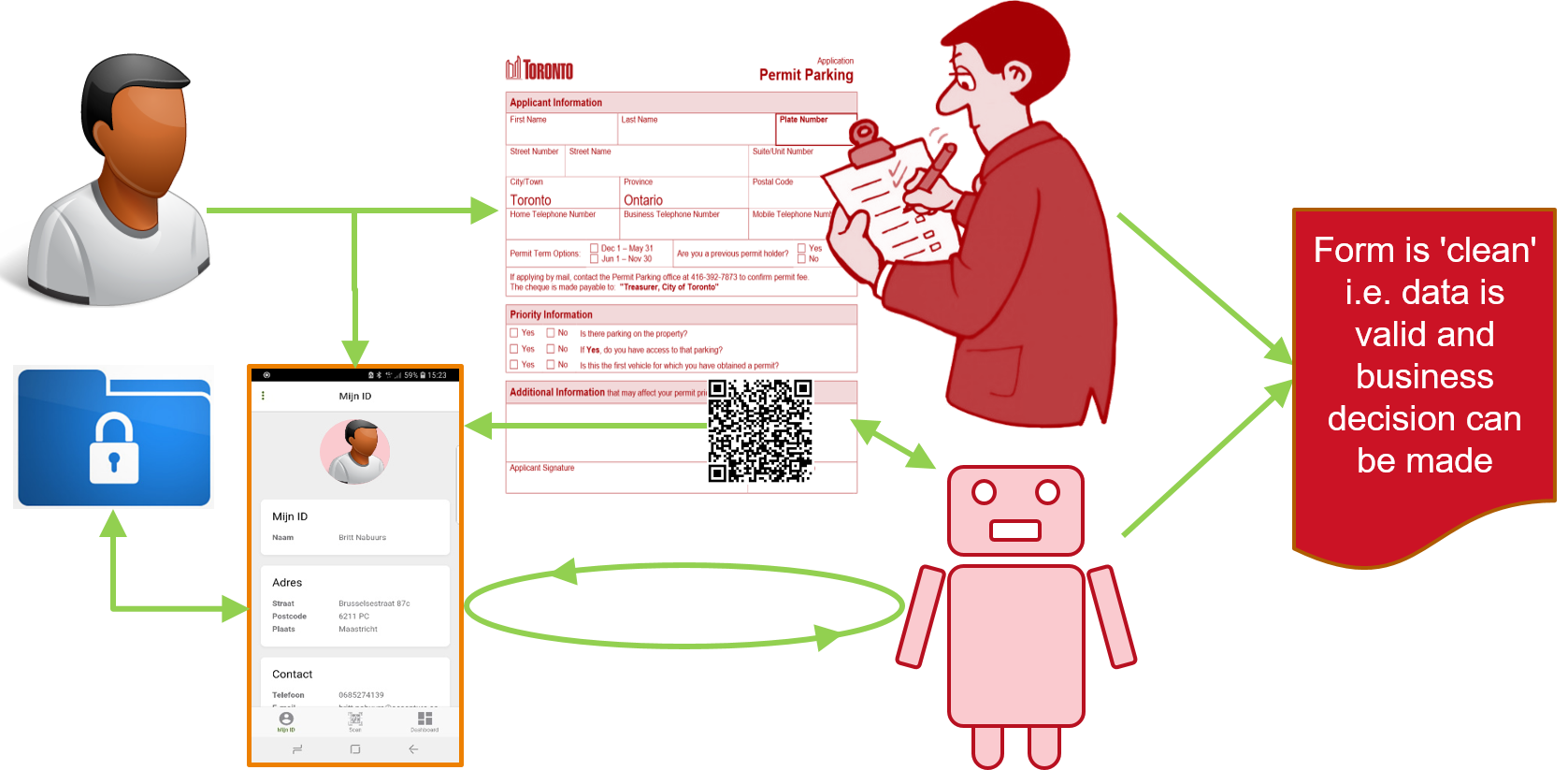

The figure below is a high-level visualization of the filling in and validation parts:

Figure 1. High-level visualization of the filling in and validation of a form.

Figure 1. High-level visualization of the filling in and validation of a form.

The transaction that is envisaged here is the issuing of a parking permit. Participants are a person (requestor) that requests such a permit, and an organization (provider) that can issue such a permit. The requestor has one electronic agent, the Requestor Agent (RA), i.e. an SSI-aware app on their mobile phone that can access a secure storage that contains 'credentials', i.e. data that is digitally signed by some third party, thus attesting to the truth of that data. The provider has two agents: one is an SSI-aware component Provider Agent (PA_ that works with the web-server that presents the form, and the other is a person P whose task is to validate any data (on behalf of the provider) that is not validated electronically. The form itself contains a means, e.g. a QR-code or a deep-link, that allows RA and PA to set up a secure communication channel (e.g. SSL, DIDComm) and agree on the specific form that needs to be filled in.

After the RA and PA have established a communication channel and agree on the form to be filled in, PA informs RA about the information it needs to fill in the form, and the requirements that this information should satisfy1. RA then checks its data store to see whether or not such data is available, sends such data to PA, which subsequently validates it and uses it to fill in (appropriate parts of) the form. Finally, P validates the remaining data, which either results in a 'clean' form, i.e. a form that contains valid data that can subsequently be used to decide whether or not to provide the parking permit, or a message to the requester informing him about missing and/or invalid data.

When the transaction has been completed, both participants can issue a credential that attests to the results of the transaction. For example, the provider could issue a credential stating that the requestor has obtained a parking permit for a car with a specific plate number (and other attributes). The requestor can store this credential and from that moment on use it in new electronic transactions.

Footnotes

-

Since transactions are symmetric, the requestor could also have a form that the provider needs to fill in so as to provide the requestor with the data it needs to commit to that transaction. We have left that out of this description for the sake of simplicity. However, the eSSIF-Lab functional architecture does take this into account. ↩