Decentralized (Networked) Risk Management (NRM)

This is work in progress.

This work needs to be compared with and integrated with (or separated from) the contents of the Decentralized GRC pattern

Introduction

Traditional risk management (RM) frameworks, such as ISO 31000, COSO, or NIST 800-30 have emerged in a time where centralized organizational leadership and auditing, and cyclic (PDCA) processes for risk management, were prevalent. Most (large) enterprises have adopted (a mix of) them, and many have been certified (e.g. against ISO 9001 or ISO 27001) thereby demonstrating they govern and run the associated risk management processes as intended, and are compliant with such standards and often also with applicable regulations.

While useful, these frameworks don't provide actual/practical guidance for all situations. For example, it is well-known that SMEs or other parties that do not have the required (expert) knowledge, time and other resources to setup and run elaborate processes for managing their risks, are pretty much left to their own devices. Also, larger organizations that use these frameworks need additional mechanisms to ensure that the risk objectives set out by the board are actually realized in the 'operational cellars' of the organization.1

We provide another way of thinking about risks. It is based on the postulate that parties are autonomous entities, that pursue their owns objectives, that perceive the associated risks, and set risk objectives to ensure these risks are managed. While this may not seem to be all that different from what traditional RM frameworks do at a first glance, there is a big difference between parties that realize what it means to be a party and how that limits their scope of control, and parties that do not. It's about their realization where they can exercise their autonomy and where they can - at best - exercise influence.

Purpose

Decentralized Risk Management (also called Networked Risk Management (NRM)) is a risk-management process that has been designed for parties that are aware of their autonomy and its limitations, which implies they are committed to use the parts of the eSSIF-Lab terminology that are relevant here (the terms that are emphasized and come with popups in this document). They can use it to manage their risks, i.e. the risks associated with their owns objectives, regardless of whether it is consciously or unconsciously aware of them (we assume that most of them are of the 'unconscious' kind).

NRM is decentralized because every party runs it on its own, within its owns scope of control. In an organization that is a hierarchy of sub-organizations, such as departments, it is typical that every sub-organization (e.g. the board, the finance department, the security department, divisions, etc.) manages its owns risks, and none other than these. We will see that this setup is capable of producing the result that all risks in the organization are properly mitigated, and the overall residual risks are acceptable.

Traditional risk management and NRM

Processes exist to realize (the results associated with) objectives. We use the term risk objective to refer to the objectives that a party owns for the purpose of creating and/or maintaining a state of affairs where the set of the risks it owns is acceptable, which means that no immediate action is required. That then is the purpose of the risk management process described here. Note that since risk objectives are also objectives, they too come with an associated risk that may need to be managed.

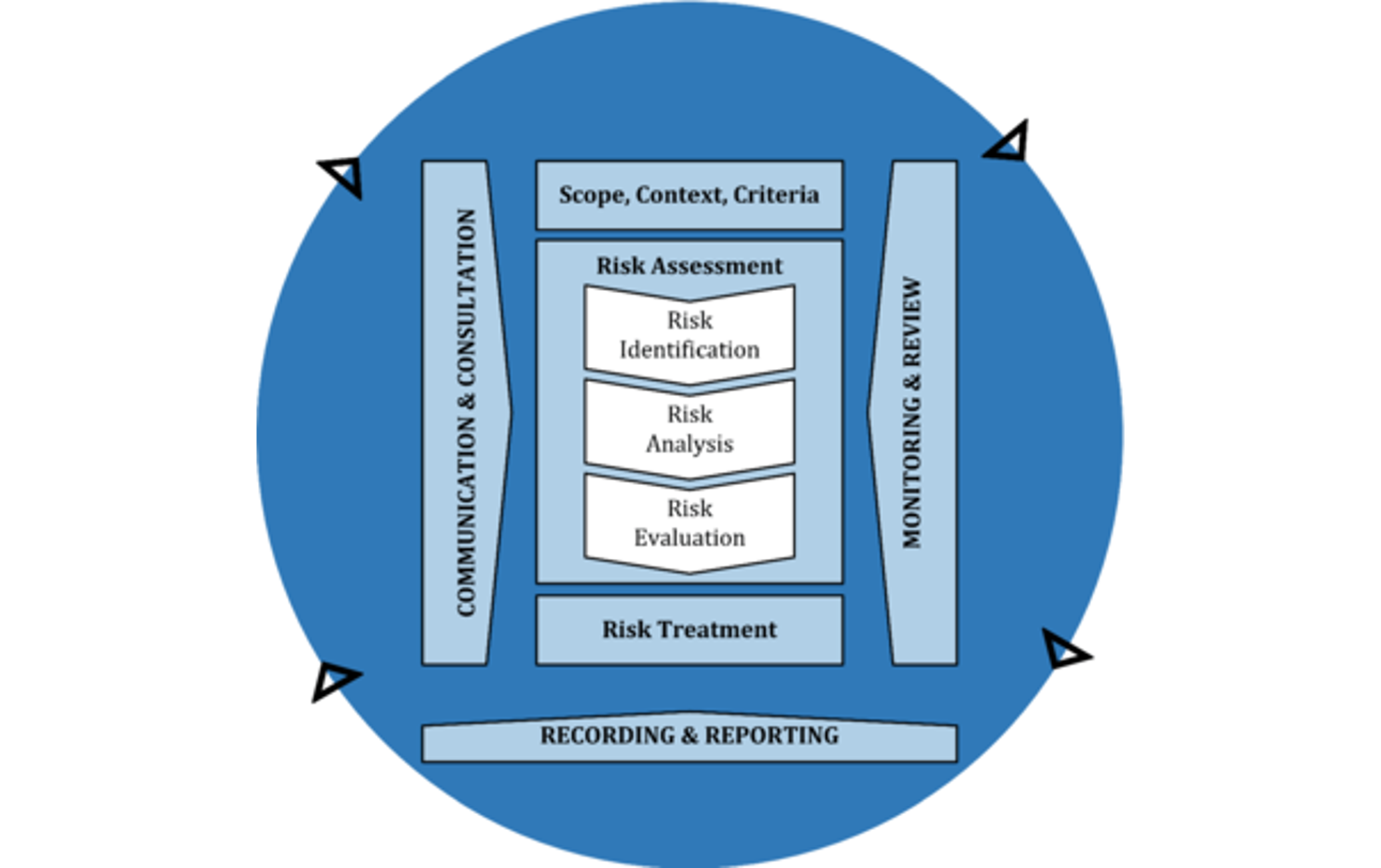

The following figure from ISO 31000:2018 shows a generic risk management process that is very similar in nature as the ones presented in other standards:

Figure 1: Activities in a generic risk management process (source: ISO 31000:2018).

Figure 1: Activities in a generic risk management process (source: ISO 31000:2018).

Note that the process does not show how activities are sequenced (as often encountered in figures of other standards). That is because in practice it is iterative: an activity is executed because there is a need for its result to be used rather than because it's its turn to be executed (as in sequential specifications).

What is characteristic for NRM Is that we assume that the risk management process that we describe is being run by (or on behalf of) a single party. This means that every activity is executed by (or on behalf of) that party, and all necessary policies, e.g. for executing such activities, are created and maintained by that party. Also, all objectives and risks that appear are owned by that party.

In the following sections, we will describe these groups of activities by summarizing what ISO 31000:2018 says about them, and devise generic objective descriptions that parties can refine for themselves so that they become practical for use in their own risk management process. Then, we proceed to describe the consequences of applying the NRM characteristics (as mentioned above) for that set of activities. For additional texts pertaining to ISO 31000, you may visit ISO's online browsing platform, which allows you to read this standard online, for free.

Scope, Context, Criteria

This is a group of activities that aim

- to determine what is, and what is not to be considered dealing with within the risk management process (scope).

- to create and maintain a state of awareness in which the party has sufficient knowledge about the world it operates in (context).

- to define (an initial set of) 'risk criteria', i.e. criteria that are to be used to evaluate the significance of risk and to support decision-making processes (criteria).

From the NRM perspective, the scope is (a subset of) the set of objectives that are owned by the party that executes the risk management process, including the management and/or governance processes for each objective, and the (operational) processes and resources for producing and/or consuming the associated results. The scope includes three kinds of objectives:

- 'expectations', i.e. objectives the result of which is consumed, but not produced by the party itself;

- 'obligations', i.e. objectives the result of which is produced by the party itself and consumed by (at least) one other party.

- 'controls', i.e. objectives the result of which is produced and exclusively consumed by the party itself.

In NRM, the context initially exists of the knowledge that the party already has about the world it operates in; any additional awareness that is required will follow from the party feeling a need. We assume that the need will be appropriately accommodated for by managing the risk for the objective that aims to maintain an appropriate awareness of the world the party lives in. The context includes an awareness of the party's 'stakeholders', i.e. any party that produces and/or consumes results associated with an objective of the party itself.

Risk Assessment

Risk Assessment is the core activity of all risk management processes. There are (slight) variations in how this is subdivided. For example,

- ISO 31010 specifies the following sub-activities:

- Risk Identification.

- Risk Analysis.

- Risk Evaluation.

- NIST SP 800-30 rev 1 (2012) has:

- Identify Threat Sources and Events;

- Identify Vulnerabilities and Predisposing Conditions;

- Determine Likelihood of Occurrence;

- Determine Magnitude of Impact;

- Determine Risk.

Within NRM, we have the following sub-activities:

- Risk Identification, i.e. the process that leads to the result where the party is consciously/explicitly aware of all the risks and the associated objectives that it owns, and that need to be actively managed - that is: analyzed and evaluated.

- Risk Analysis, i.e. the process that leads to the result where the party disposes of all information that enables it to evaluate the condition/status of the objectives and associated risks (e.g., risk levels) as it currently stands - from different perspectives if appropriate. It answers the question: "How come the status of the objectives, and the assessed risk levels, are as they are?".

- Risk evaluation, i.e. the process of determining where additional action is required, and what that action then might be, e.g. leave it as it is, change objectives, change one or more of an objective's control objectives, etc.

Risk Treatment

In ISO 31000:2018, risk treatment is an iterative process that consists of formulating and selecting risk treatment options, planning and implementing the chosen ones, assessing their effectiveness and re-iterate if the remaining (residual) risks are acceptable.

In NRM language, this corresponds with the governance (i.e. the creation and maintenance) and subsequent management (design, implementation and operation) of control objectives for the purpose of ensuring that risks are being treated effectively.

The other two activities, 'Risk Communication and Consultation', and 'Monitoring and review' are not activities like the others in the sense that you continually have to communicate and consult with your stakeholders and advisors so that they can help you reach your objectives (and vice versa) and make good judgements and choices. You also need to continually monitor and review (the changes you have made in) the ways you work, the tools you use, and the context that you are in so that you will notice when risks arise that may not/no longer be acceptable, which will lead to a review of your context (context establishment) and a subsequent risk assessment.

Communication and consultation

ISO 31000:2018 says: "The purpose of communication and consultation is to assist relevant stakeholders in understanding risk, the basis on which decisions are made and the reasons why particular actions are required. Communication seeks to promote awareness and understanding of risk, whereas consultation involves obtaining feedback and information to support decision-making."

In NRM, the stakeholders are parties that are expected to produce results that the party itself consumes, and parties that consume the results that the party itself is committed to produce. In other words: the parties towards which the party itself has an obligation and/or expectation.

A proper administration of the objectives it owns enables a party to simply compose a complete and up-to-date list of all of its stakeholders, and for each of them, a list of the expectations and obligations the party has towards that stakeholder, which determines the scope of any communications between them. If a stakeholder does the same, it becomes easy for them to compare notes as any expectation that one party has towards the other must match an obligation that the other has towards this party - and vice versa. Their communication basically consists of informing the other about how the party that has the obligation to produce a result can match the expectations of the consuming party, thus ensuring the produced results are fit for the purposes of the consuming party.

In NRM, consultation is done in two ways. The first one is where parties communicate, and inform each other of what they are doing or expecting. In real life experiments, such communications have shown to also have consultation aspects, based on the expertise that each party has.

The second one is where the advise itself is the product, implying that the consulting party produces the advise as a result of an obligation it owns, which must then match the expectation of the party that requests such advise. Thus, apart from explicitly creating an expectation to obtain some specific advise, this is not all that different from the first way of communication as stated in the previous paragraph.

Monitoring and review

According to ISO 31000:2018, the purpose of monitoring and review is to assure and improve the quality and effectiveness of the risk management process design, implementation and outcomes.

Effectively, this is what we call governing the risk management process, which entails the specifications of objectives that state the results by which a party determines that the risk management process design, implementation and outcomes are as (s)he would like them, or expects, to be, and subsequently managing these objectives.

Recording and reporting

ISO 31000:2018 says that recording and reporting aims to communicate risk management activities and outcomes across the organization, provide information for decision-making, improve risk management activities and assist interaction with stakeholders, including those with responsibility and accountability for risk management activities.

From NRM perspective, the recording and reporting is limited to whatever is needed or expected, and therefor is specified as a result of some objective. Typically, such recordings may play a vital role in governance and/or management processes, e.g. as a contribution to evaluating the objectives being governed/managed.

Doing this immediately clarifies which party produces specific recordings, which parties will use (consume) such recordings, and what purposes they should be fit for serving. This not only helps to efficiently produce recordings that are useful (i.e.: actually used), but also to identify when recordings are not, or no longer necessary so that the recording process can stop.

from here onwards, texts need to be revised

Networked Risk Management

Networked risk management is a way for managing the risks of a single party, taking into account that our definitions of risk, risk owner and other risk-related terms are aligned with those of ISO, but (contrary to those of) but there are some subtle differences. much more explicit In ISO standards, the person or entity (say: the party) with the accountability and authority to manage a risk is called the 'risk owner'.

Networked Risk Management is a management process that is run by (or on behalf of) a party for the purpose of managing the risks that this party owns.

Scoping

All (ISO and non-ISO) frameworks start by requiring that you define the scope (also called 'context') of your management processes. And for good reason: you will be in charge of whatever you will be managing in such processes. To this we add the requirement is that

- a context must have a single owner, i.e. a party that is in charge of what happens in that context, and that consequently should be managing the risks therein.

- a context must fall within the scope of control of its owner, as it is hard to manage risks or other things if you cannot control them.

In decentralized contexts we deal with ecosystems of autonomous ((self)sovereign) parties, it is a given that the scope of control of each such party does not extend beyond the party itself - it's the very definition of autonomy/sovereignty. A party could use an ISO standard to manage X (risks, ...), but SHOULD limit its scope to be within its own scope of control. The only guidance that such a party gets from ISO standards regarding how to deal with risks that relate to stuff outside the scope, are the 'identification of 'interested parties' (that may work with you, or against you) and 'communication' (about the topics you are managing). I think that ToIP governance should be aware of this pitfall and SHOULD NOT attempt to create or support frameworks that are meant to be used to do governance over autonomous parties. Rather, the WG/TF should focus on doing governance that assists such parties as they autonomously make their own, subjective decisions that are good for them individually, but perhaps not so good for others. That's a challenge. But if we succeed here, this can be a real contribution, not only for ToIP, but also for the various management standards in ISO. So we don't do away with such standards, but we complement them by providing ways to deal with larger, decentralized contexts of autonomous parties. Secondly, governance and trust assurance should not be limited to IT security (ISO 27001, ISO 27005). It should also cover business risks, e.g. of a business transaction going sour. After all, I think that a large part of data in credentials that are being exchanged serve to provide information to parties that are negotiating/conducting a business transaction, so that they can (subjectively/autonomously) assess their individual transaction risk(level)s, and mitigate such risks such that the residual risk becomes acceptable. This, and other topics, aren't covered by ISO 27001 nor ISO 27005. So we should take a broader look than these.

Traditional risk management (RM) frameworks are currently not fit for use in decentralized contexts. Frameworks such as ISO 31000, or COSO, (tacitly) assume centralized organizational leadership and auditing, and cyclic (PDCA) processes for risk management. While predominantly large enterprises have adopted (a mix of) them, it is way too cumbersome for SMEs and individuals to work with. Also, their being adopted by enterprises suggests they are inappropriate in decentralized, networked contexts. This paper proposes a way for identifying and managing risks and doing the associated governance and compliance in a way that is appropriate in such contexts.

Introduction

Perhaps the best known approach is based on Assets Threats/Hazards and Vulnerabilities (ATV). It starts with making an inventory of the party's assets (things that are valuable to that party), list the threats to such assets (ways in which they lose (part of) their value), and vulnerabilities (weak spots in assets that increase the likelihood of threats being effective). Then, the likelihood of such threats occurring may be assessed, as well as the impact (often: damages) they would have. Combining these two enables a party to assess its risk levels. For the risks that are unacceptable, a treatment plan must be conceived, the execution of which supposedly reduces (or: gets rid of) the risk. This, but also: changing circumstances, change the risks the party runs, which means that it has to repeat all these steps in a continuous management cycle. Mature RM-processes will also include other things, such as communications with the party's stakeholders, regular audits, etc.

Another well known method, predominantly for industry, is bowtie. It focuses on events that may occur, a 'fault tree' (i.e. a graph that identifies the relevant causes/threats) and an 'event tree' (i.e. a graph of possible consequences/outcomes). The have the 'barrier' concepts, which represents a measure that aims to prevent threats from materializing, or reduce the effect of possible consequences. As with ATV, implementing/changing measures, as well as changing circumstances, require set of events and graphs to be appropriately managed. This entails deciding about the (un)acceptability of unwanted consequences, and implementing barriers as needed - which change circumstances.

RM approaches such as the ones mentioned above have severe practical limitations. Individuals and many SMEs do RM intuitively, they 'know' where the risks are that need to be mitigated. They consider such approaches as an inefficient way of finding out what they already know. In large organizations, we've seen lots of activities being conducted in order to comply with the RM-process requirements, but did not contribute all that much to managing actual risk.

An illustration of this is an incident that took place in January 2012 at the Dutch telecom operator KPN. IT security has long been an IT priority for KPN: its CEOs are member of the 'Cyber Security Raad', a national and independent advisory college of the Dutch government whose mission is to increase cybersecurity throughout the country. Also, its critical services have been certified against ISO 9001 and ISO 27001. Notwithstanding all this, a 17 year old boy broke into hundreds of servers, where he could have manipulated KPNs fixed telecom network putting the reachability of the national emergency number 112 (911 in the US) at risk. The question here is why the traditional methods were unable to prevent this from happening.

Another illustration comes from the OWASP Top 10 list of web application security risks. This list, which exists since 2003 and is regularly updated, shows that the variety of vulnerabilities in applications does not change all that much: injection, broken authentication, cross-site scripting, using components with known vulnerabilities are here to stay. The question here is what is missing in the RM processes of small and large organizations alike that makes many of them deploy systems with such vulnerabilities, in spite of the vast amount of guidance that OWASP provides for preventing them.

One reason for this may be that risks must be owned. That is to say: there must be a person (not: an organization) that actually feels 'pain' (discomfort, anxiety, ...) when that risk is not acceptable. This is a different kind of ownership than what we have seen a lot, which is writing the name of a person next to a risk. The latter is ineffective if that person doesn't feel the associated pain.

Another reason is that the number of risks a person needs to deal with must be manageable. CRAMM (1985-2003) is a RM method + tool that helped organizations do their risk assessments by providing threats to, and vulnerabilities of, various kinds of assets. As the number of technological products exploded, so did their database, resulting in a CRAMM risk assessment becoming unacceptably costly and long. Also, it produced ever more mitigation measures. For managers, it was obvious that many of them were irrelevant and the required budgets would not be available.

A third reason is that risks should be relevant in order to be treated. For example, the risk of leaking a cryptographic key from a crypto chip that is vulnerable to power/timing-attacks is irrelevant e.g. when the chip and its battery are sealed in a physical casing. Also, the risk of crashing your car as a result of an autopilot failure is irrelevant if you never use the autopilot.

The last reason we mention is that people generally prefer activities that help them realize their objectives rather than activities that do not (visibly) contribute. Many governance, RM and compliance (GRC) related activities fall in that second category, except perhaps for people whose job is 'doing GRC'. Having to do such activities is a typical trait of centrally organized GRC.

The alternative for putting effort in preventing failures is focusing on the flip-side of that coin, which is: putting effort in realizing successes. It stimulates people to own the associated risks and manage them (it makes the pain go away). When the risks become unmanageable, the associated pain may indicate you have an objective of staying healthy, which you might mitigate by outsourcing the realization of one or more of your objectives.

To illustrate the difference between these approaches, consider a doctor whose objective is to get her patients in a continuous healthy state and keep them there. When a patient is not in such a state, she won't inventory everything that could be wrong with the patient as traditional methods would have her do. Rather, she looks at what is preventing the patient from becoming/remaining healthy, makes a treatment plan, and has it executed.That's much easier. And when she needs to see too many patients, she (literally) feels the associated agony and will try to offload some of the patients to trusted colleagues.

Realizing successes is an inherently decentralized concept, because in the end, being successful always depends on some kind of recognition of others: if you provide a service or product, your success depends on the value they have for your customers, which they express by paying you money, or providing you with a service or product of their own. Positive motivators stimulate parties to increasingly interact and work together to the benefit of both. In contrast, centralized settings have a tendency to use negative motivators to make people interact and work together.

Different methods have been around for some time now that may be part of decentralized GRC (and in particular: decentralized RM). One such method is the Open Group's Dependency Modeling standard (DM - also available on ResearchGate). It specifies a way by which a party can inventory its goals, and compute the probabilities of achieving them by combining the probabilities of the goals that they depend on. Statistical operations then identify points (objectives) of failure that need to be addressed.

Another, complementary method is Networked Risk Management (NRM). Next to the role of 'objective Owner', NRM adds two others: the Producer is the party that is responsible for realizing the results by which it can be established (e.g. by an auditor, or customers) whether or not an objective is met/realized/fulfilled. A Consumer is a party that uses these results for the purpose of realizing one or more objectives that it owns. An objective Owner states the objective, specifies the (auditable) results, and must be the Producer and/or Consumer thereof. Risks are associated with an objective, and map the objective to a risk level, i.e. a measure that is meaningful to the owner and that indicates the extent to which the objective is not (going to be) met. Pragmatically: the amount of 'pain' (discomfort, anxiety, ...) the objective's Owner experiences as it contemplates the chances of it (not) being realized.

In analogy to 'Self-Sovereign Identity' - a term used to refer to the sovereignty/autonomy of individuals (and organizations) when it comes to identity-related matters, we introduce the phrase 'Self-Sovereign GRC' to refer to the sovereignty/autonomy of individuals (and organizations) when it comes to setting their objectives (governance), managing the associated risks of (not) realizing them (risk management), and doing what is necessary to become and/or remain part of a community of other self-sovereign entities (compliance).

The purpose of this paper is to help the reader understand what this is all about, so that we can apply the ideas that are deemed useful in the ToIP Governance Stack Working Group. ideas in the better explain NRM-based risk management, NRMBecause of its focus on NRM is ideally suited for decentralized contexts.

Mental Model

This chapter describes the mental model for decentralized risk management. The model uses eSSIF-Lab terminology, in particular that which is related to Parties, Actors and Actions.

Summary

This mental model captures the foundational concepts and relations that we need for thinking about decentralized risk management. It answers questions such as "What is a risk?", "Who is to address what risks?", "What's in it for me?", "How do the terms 'Governance', 'Risk management' and 'Compliance' relate to one another?", and more.

The model acknowledges the sovereignty (autonomy) that parties have in their

- governance, i.e. as they decide which objectives to pursue, how to organize their realization, how and when to change or update their objectives, etc.

- risk management (RM), i.e. identify the assess the

Notes

Footnotes

-

The Dutch Cyber Security Council is an advisory body for the Dutch government, providing it with advise regarding all sorts of cyber security related matters. Back in 2013, it was chaired by the CEO of KPN, the leading Dutch telecom operator. Being highly aware of cyber security and associated risks, KPN had a framework in place, and was certified against ISO 27001. In spite of all this, a 17-year old script-kiddie broke into IT systems of KPN in the beginning of February, which enabled him to intercept internet traffic and manipulate the telephone network to the extent that the emergency call number 112 could have been rendered out of service. (One of the news items (in Dutch) is at Tweakers). This case demonstrates that there is a difference between an organization having information security awareness at the top management level, having an information security management system in place, and being certified against ISO 27001, and on organization that effectively ensures that (in its 'operational cellars') security updates for (crucial) software are actually installed. ↩