Parties, Actors and Actions

This pattern captures the essence of how things are done. It answers questions such as: "Who/what does things?", "How are their actions being guided/controlled?", "Who controls whom/what?", "Who/what may be held accountable?". These questions need to have a precise answer if you want to design or implement systems where actors can be anything, ranging from programs/apps running on computers as well as humans. This pattern provides a way of looking at organizations, people, and non-human actors. It shows how they interact with one another, and how they may or may not work for one another. The pattern describes how parties are '(self) sovereign' as they construct their own world view, reason with that, and make their (subjective) decisions autonomously. It also shows how this knowledge is used, where it is used, and also: where it is not used. The latter implies that parties have a limited scope of control, which gives rise to their need to work together with other parties, that have their own sovereignty. Such interactions with others, however, are outside the scope of this pattern.

Purpose

In order for people or organizations to decide what to do (themselves), what to ask others to do (for which these others generally require some form of compensation, how to know that the associated risks are worth taking, this pattern provides a simple mental model that provides the basis for thinking/reasoning about such questions. The pattern is expected to be helpful to those that think about designing complex systems (systems of systems) that are owned by different parties, and in which both human and non-human actors take part.

Introduction

One may readily observe that in some way, people and organizations are similar. This is indicated e.g. by the notion of 'personality' that many legal jurisdictions assign to (specific kinds of) organizations. They can both be assigned rights and duties, be held accountable, and subjected to prosecution: they can sue and be sued.

People and organizations are also different. People qualify as actors, meaning that they can actually do things. People can drink beer or sign contracts, which organizations cannot. Organizations need actors to do things on their behalf. Still, it is a common and accepted practice to say something like "TNO has signed a contract", as if TNO were an actor. There is no problem with that, as long as we interpret such phrases to mean that the organization that is said to act is actually using an actor that acts on its behalf. So, "TNO has signed a contract" means that some actor exists that has signed the contract on TNO's behalf.

So what is the characteristic that people and organizations actually share? It is the fact that each has its own, subjective knowledge, which it maintains in an autonomous, sovereign fashion, and the means and ways to maintain that knowledge, i.e. to acquire, generate or change its knowledge, reason with it, make decisions (e.g. as to what constitutes a valid logic (= way of reasoning), what is (not) true, what (not) to trust, etc.). Of course, organizations will need actors to do the actual work, but the resulting knowledge is that of the organization.

We use the term party to refer to entities that autonomously maintain a specific knowledge, the typical examples of which are then people and organizations. The relevance of this is that all decision making, information processing and the like, which is inherent to a knowledge, must therefore be linked to the entity that maintains it (i.e.: a party).

This mental model is about how parties and actors relate to one another, and how actions are executed by an actor on behalf of, and using the knowledge of, a party. The relevance of modeling this somewhat formally is that it will make it easier to build IT systems, where IT (that is running) qualifies as actors, and people and organizations (businesses, enterprises, governments) qualify as parties. We like to think this mental model contributes to bridging the gap between business and IT.

Formalized model

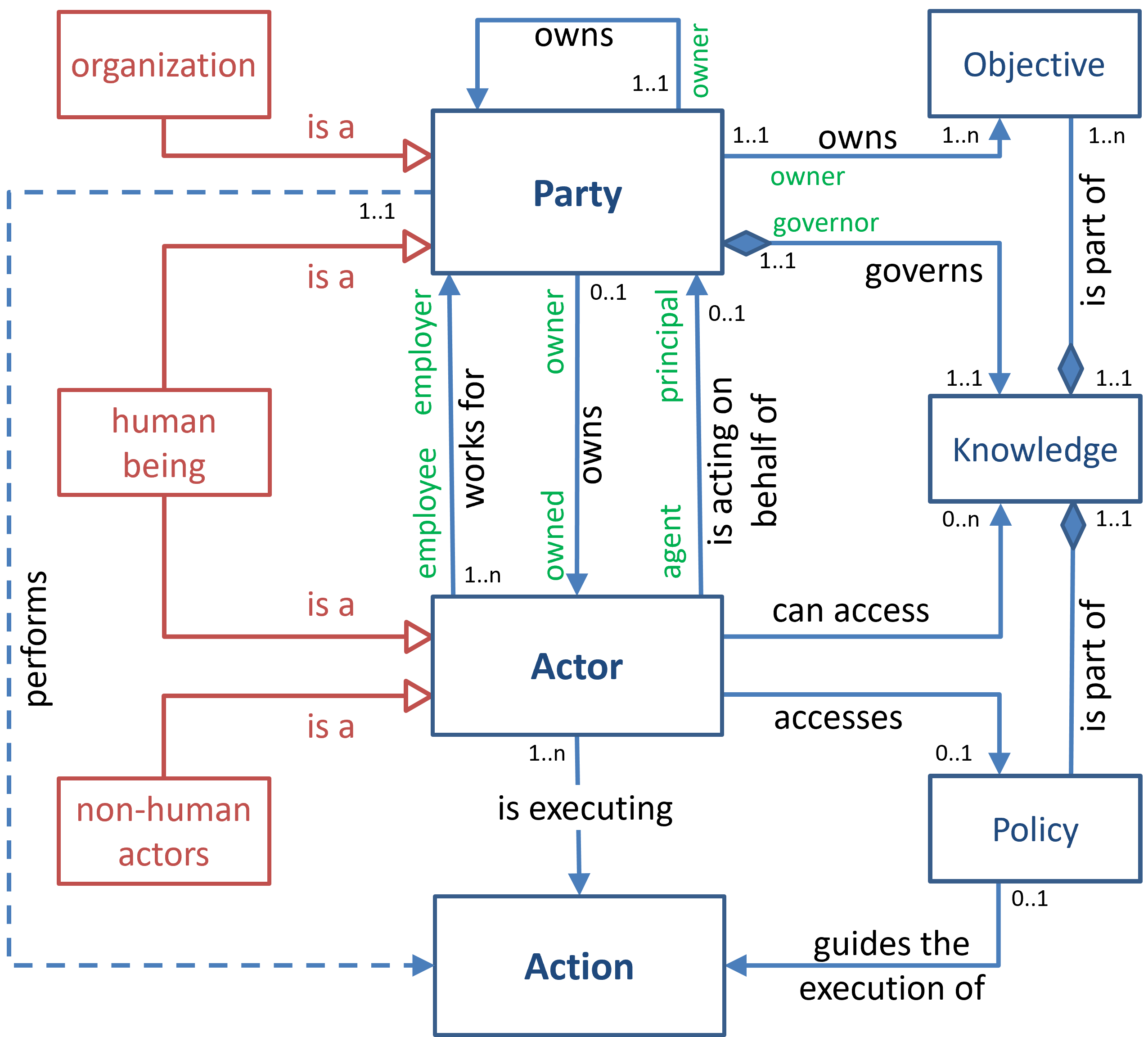

Here is a visual representation of this pattern, using the usual notations and conventions. Please not that in this pattern, the relation 'is acting on behalf of' has synonyms in other patterns, including 'acts on behalf of', 'is executing on behalf of', 'executes on behalf of', that should not be confused with the 'works for' relation (as further explained below).

Organizations, human beings, and non-human actors

The model shows how we propose a change in perspective, one in which we no longer distinguish between people and organizations, but rather between parties and actors. The figure shows that organizations and humans both qualify as parties, and that actors consist of humans and non-human actors.

We already mentioned that organizations are not considered to be able to act: they need an actor (human or non-human) to execute actions on their behalf. For a human, this means that we can say that it is acting on behalf of itself, which is readily verifiable. However, this model explicitly allows humans to also act on behalf of some other party: another human being or an organization. Finally, for non-human actors (e.g. robots), this means that any action they may execute must have some party on whose behalf the action is executed.

Parties, actors and ways they relate

When an actor is acting on behalf of some party, we mean to say that it is actually in the process of executing a (single) action, which it executes on that (single) party's behalf. These constraints (a single action and a single party) allow for:

- assigning accountability for the execution of that action to a single party;

- that party to devise a policy that specifies how that action is to be executed;

- an actor to execute different actions on behalf of parties (i.e.: to multi-task for different parties), executing every action in the way that the respective parties expects.

In this mental model, we specify three ways in which parties and actors can relate to each other:

-

The relation

is acting on behalf ofsays which actor is executing some action on behalf of what party. It is not relevant what the action is, as long as there is one. In this relation, the actor plays the role of agent (of that party), and the party plays the role of principal (of that actor). So, for every agent-principal pair, an action must exist that the agent is executing on behalf of its principal. Thus, this relation models what one might call 'operational representation' (see the party-representation pattern for further details). -

The relation

ownssays which party has a legal or rightful title to control (own) the actor. This would e.g. be the case if the actor were a computer program (a running mail client or mail server, or an app running on a mobile device). We use the term 'owns' to relate a party with an actor for which this is the case. In this relation 'owns', the actor plays the role of the owned, and the party plays the role of the owner.

Note that there are also other relations called owns, which always has a party that plays the role of owner, but there are various entities that can be owned.

- The relation

works forrelates the actors and parties for which it is realistic that the actor might act on behalf of what party. In this relation, the actor plays the role of employee (of that party), and the party plays the role of employer (for the actor). An obvious example is where a person is employed by some organization. However, we also use this relation for non-human actors (e.g. robots, computers) that might act on behalf of some party. We use the term onboarding for the process by which an actor gets towork fora party. This process produces an employment contract that specifies the rights and duties between the party that controls or owns an actor and the party that needs the actor as one of its 'employees'.

Actions, policies and objectives

Every party has its own mission (calling, vocation), and realizing that is often perceived as the reason for its existence (its "raison d'etre"). This is what drives them. It causes the party to set its (other, derived) objectives, and determine how to realize them, e.g. by specifying the (units of) work, (i.e. actions) that produce the associated results, and by employing actors that are capable and suitable to do that work.

Actions are executed by a specific employee in a specific context, i.e. a specific place and time, on behalf of a specific party. The fact that parties are autonomous suggests that each of them will have its own idea about how an action needs to be executed. Thus, we say that a party can devise policies (as part of its knowledge) that provide the rules, working-instructions, preferences and other guidance that enable its employees to execute actions on its behalf in the ways it expects them to.

This does not imply that employees cannot use knowledge from other sources (parties) as well. In particular, human employees can be relied on to have knowledge to which artifacts such as certificates and diploma's testify. Non-human employees may also be certified, or come with documentation stating their capabilities and capacities. Policy authoring is thus a balancing act between the kinds of knowledge that a party can rely on its employees to have, and the additional guidance they would need if they are tasked with executing specific actions, so that the results thereof are 'fit for purpose', i.e. contribute to the realization of objectives as the party expected.

The design of actions, the onboarding of suitable actors, their task assignments and results they produce are all subject to uncertainty that contribute to risks. Risks and the management thereof is discussed in the Governance, Risk Management and Compliance (GRC).