Governance and Management

This is work in progress, and needs to be reviewed. If you want to comment, please raise an issue.

Purpose

The Governance and Management pattern captures the concepts and relations that explain how parties organize that their objectives are realized, either by doing the associated work themselves (management), or by arranging for other parties to do that (governance). The contribution of this pattern is to show how this is done, based on the idea that every objective is owned by a single party.

Introduction

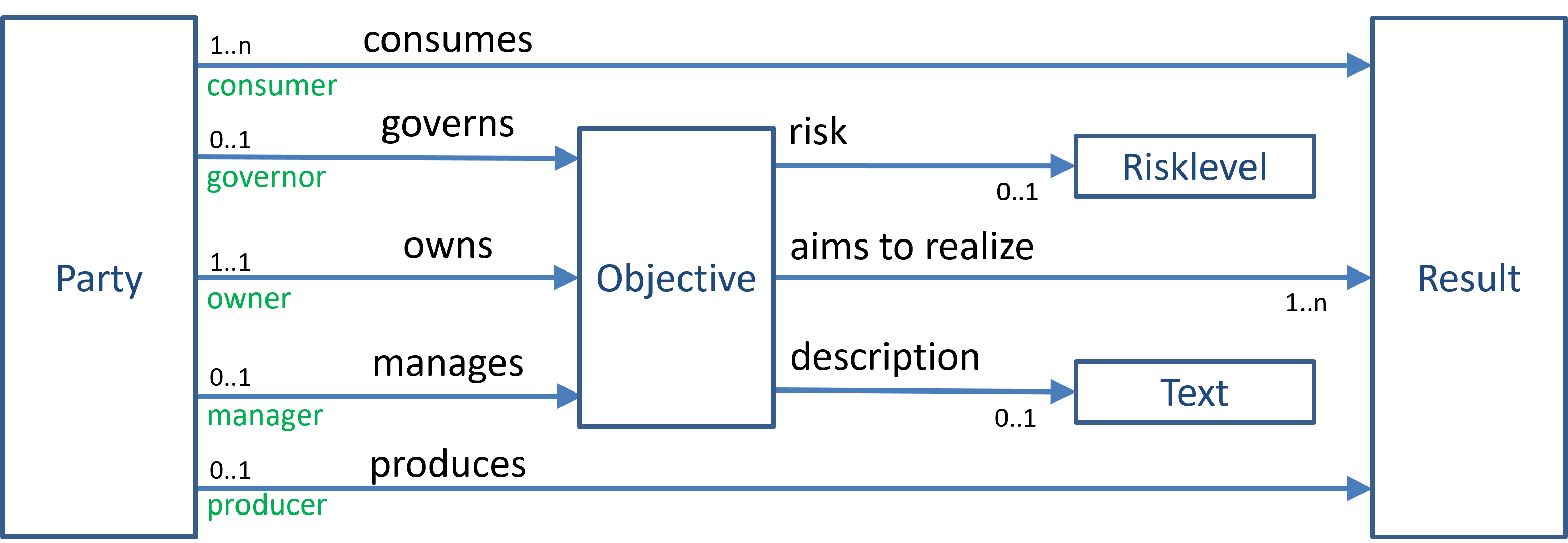

Whether or not an objective is realized can be seen by the status of the associated results, as is explained there. The following figure is a recap of the objective-concept (using the usual notations and conventions):

Figure 1. Parties and their objectives.

Figure 1. Parties and their objectives.

The core property of this model is that every objective has precisely one owner, which is the party that pursues the realization of the associated results, from one (or both) of the two following perspectives:

-

the production, supply, or management perspective. This is the perspective in which the owner of the objective will itself be managing the creation (or maintenance) of the results associated with the objective. This entails the creation of (product) specifications and working instructions, organizing that budgets and other production resources become available and are planned, and everything else to ensure the results will be ready to be provided to parties that will actually use them. This may include developing performance indicators, i.e. gauges that measure how well the resources are spent in this production/maintenance work, which may help managers to do their work. We will use the term 'management' to refer to these activities, and the term 'manager' to refer to the role of a party that performs such activities.

-

the consumption, demand, or governance perspective. This is the perspective in which the owner of the objective wants to actually use the results associated with the objective. This entails specifying the kinds of results as well as criteria that such results must satisfy (or are nice to have satisfied) in order to be fit for the purpose(s) that the owner wants to use them for. Such criteria may pertain to timelines (deadlines), security, quality, sustainability, etc. This may include developing 'effectiveness indicators', i.e. gauges that measure how 'fit' the results are to be used/consumed for the intended purposes, are also part of this governance. We will use the term 'governance' to refer to these activities, and the term 'governor' to refer to the role of a party that performs such activities.

Governance and Management

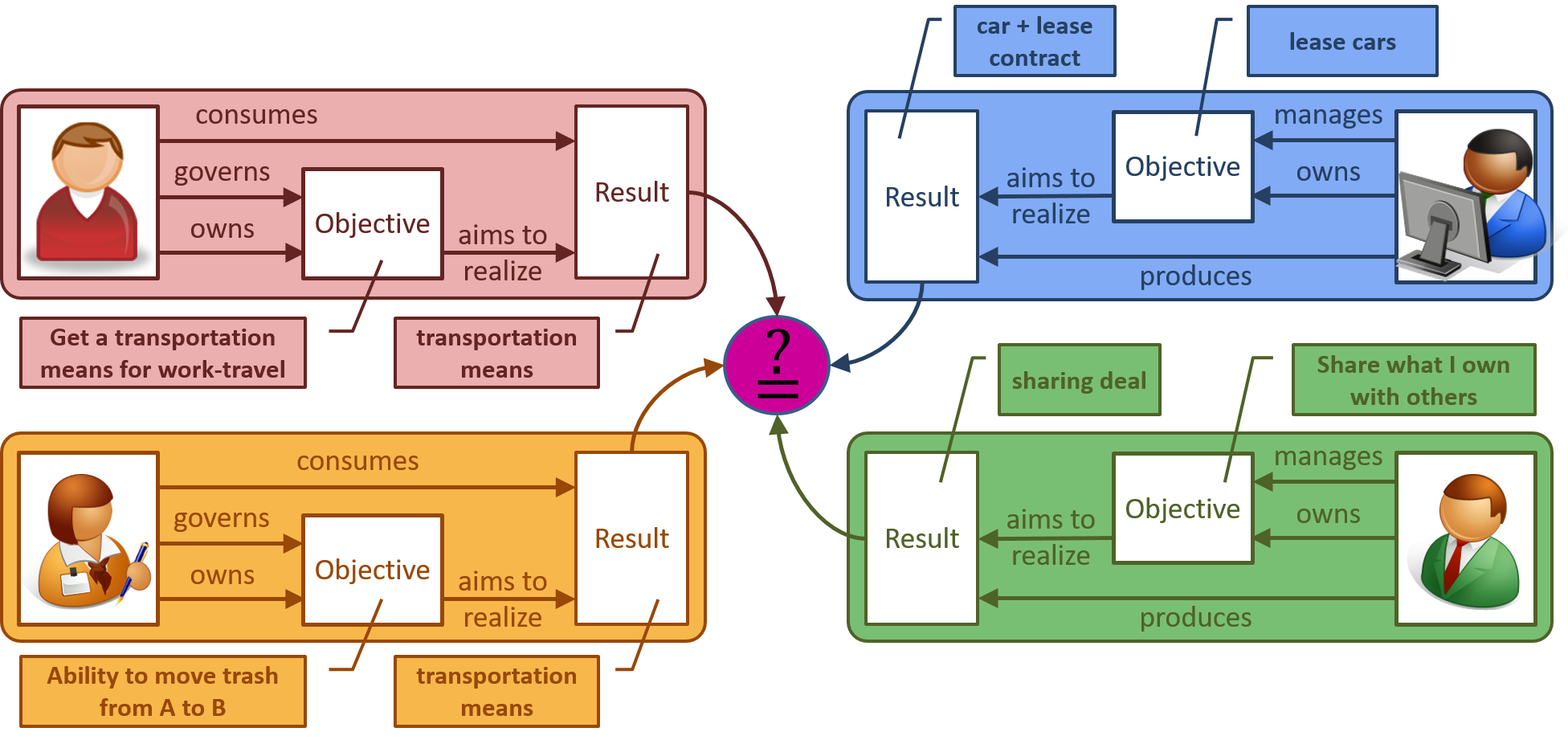

When a party both manages and governs an objective, it is in full control of the production and the usability of the associated results. This is easy to do when compared to the situation in which a party either manages or governs its objective, but not both. This governance and management pattern focuses on the latter situation. The following figure illustrates this situation:

Figure 1. Governing and Managing objectives.

Figure 1. Governing and Managing objectives.

The figure shows four parties, distinguished by color - let's call them Red, Yellow, Blue and Green. We assume that each party owns multiple objectives, but in the figure we only show a single one, each of which with a description that identifies that objective from the set of objectives of each party. The figure also shows one of the results associated with each of these objectives, again phrased such that the objective owner knows what this really means. So, Red governs an objective that it describes as "Get a transportation means for work-travel". The associated result "transportation means" then doesn't come as a surprise.

Red, who governs its objective can realize the result by 'scouring the market' to find a party that is capable and willing to provide things that Red qualifies as "transportation means" and that hence constitute the result it wants. Note that Yellow also needs to realize a result "transportation means", in order to realize her objective "Ability to move trash from A to B". Both Blue and Green produce results, i.e. a "car + lease contract" and a "sharing deal" respectively.

The essence of this figure is to show that parties that consume a result and parties that produce a result have a matching issue.

From the perspective of the consuming party, the result produced by a producing party must qualify as a result that it needs. Governing an objective is basically specifying a result in such a way that it is fit for purpose, i.e. realizes the objective, AND finding a result that is produced by some party that qualifies as such, and that it can obtain. For Red (and Yellow) this means that they need to determine whether or not the results that Blue and Green produce qualify, and engage with either if that is the case. If not, they must either find other producers whose results do match, or they have to find an alternative result for realizing their objectives.

From the perspective of the producing party, producing a result is only meaningful if it is actually used. Managing an objective is basically producing a result in such a way that there is (at least) one party that needs it. This is not only about producing things, but also about finding out what makes the produced result fit for the (various) purposes of (potential) consuming parties.

Matching

Matching (of (the results of) objectives) is the process in which a producer and consumer interact to establish whether or not a produced result (of the producing party) qualifies as a consumable result (of the consuming party). In other words, matching is the process in which an expectation of one party (the consumer) and an obligation of another party (the producer) are aligned, such that the produced results are fit to serve the purposes of the consumer. We say that there is a mismatch associated with an expectation or obligation of one party if there is no corresponding obligation or expectation of another party that is aligned with the first.

This matching process can take many different forms, which can readily be observed in practice. A very simple example is where a party (the consumer) has an objective to get a loaf of bread, which he decides to obtain from a baker. Thus, he needs to find a baker that he expects to produce the bread, and communicate this expectation (preferably with the fit-for-purpose criteria), so that the baker can determine whether or not 'oblige', which can either be the creation of a new obligation (e.g. in case it is very special bread that he doesn't normally produce) that matches the consumer's expectation, or it can be the choosing of an existing obligation that they both agree aligns sufficiently well with that expectation. Either way, the consumer and the baker now have an aligned pair of objectives, one being an expectation (of the consumer towards the baker) and another being an obligation (of the baker towards the consumer).

This mechanism of

- communicating an expectation or obligation to another party;

- this other party either creating a possibly matching obligation or expectation;

- both parties discussing, and changing their expectation and obligation until they either agree that there's a match, or one of them quitting the process, is the essence of the matching process. As an aside, note that this matching process constitutes a confluence of governance (changing one's expectations) and management (changing one's obligations); that may explain the difficulty that people may have in distinguishing between governance and management.

In practice, parties that communicate in the context of a matching process will typically have multiple and interrelating expectations and obligations towards each another. In the previous example, the baker will not only have an obligation towards the consumer to deliver bread, but he will also have an expectation towards the consumer that the latter will pay him some amount of money. So there are two pairs (expectation, obligation), going in opposite directions, and both pairs need to be sufficiently aligned for their respective owners to commit to them.

Relation management

One might say that a relation between two such parties is determined by the pairs of (expectation, obligation) that they have towards each other, and the judgements about, and characteristics they attribute to one another (i.e. their mutual partial identities). In the example, the consumer and baker may find that they regularly have the same expectations and obligations towards one another and that they are always fulfilled. Based on that, they may characterize each other as being trustworthy, or being a good baker/consumer.

Partial identities that are owned by a party and the risk management processes it runs, are related. A major influencer of how this party behaves is the assessment of the risk levels associated with the expectations and obligations that it has towards another, or - perhaps equivalently - by its judgements about the trustworthiness of the other, i.e. the levels of trust that it has in the other party fulfilling its corresponding obligations and expectations. And typically, the partial identity that the party owns about the other, is going to be revised based on the experiences this party has as it interacts with the other. Perhaps one may say that relation management is the management of the partial identities of parties that a party interacts with as it sets expectations and obligations towards such parties and experiences the extent to which such other parties fulfill them.

A party may decide to set objectives for the purpose of 'optimizing' the set of relationships that it has with others, the result of which would be that it would seek to preferably (if not exclusively) interact only with parties that it can trust to fullfil its obligations and expectations. Realization of such objectives would be called 'relation management', and is obviously tightly linked to the management of the partial identities.

Resilience

Resilience is the capability of adapting one's objectives (and associated behavior) as one's context changes, in such a way that its mission, i.e. its most important and valued objective(s) (which typically include one's "raison d'être" - the reason for one's existence), can continue to be realized. The objectives a party will adapt are the expectations, obligations and control objectives that serve to realize its mission.

While small changes in one's objectives (control objectives, expectations and obligations) are typically considered part of risk management, resilience is about making major changes. For example, consider a baker whose mission is to have fun and to ensure he has no more money (and worries) than strictly necessary to have that fun. At first, he decided that this meant the creation and maintenance of a bakery with a shop (a control objective for its mission), which in turn has other control objectives, and expectations (e.g. towards suppliers of flour, yeast, etc.), and obligations (e.g. towards its customers to provide them with bread, cake, etc.). If for some reason his customers no longer show up, he may decide to start baking pottery, or become a fisherman, which constitutes a significant overhaul of a (very) large part of its objectives.