Identity Pattern

This is work in progress, and needs to be reviewed. If you want to comment, please raise an issue.

Purpose

The Identity pattern captures the concepts and relations that explain how digital identities work, how this relates to (attributes in) credentials, and how all this can be made to work in SSI contexts.

Introduction

The term 'identity' is used in many ways in different contexts, and is often related to intangibles, such as feelings, emotions, ideas of belonging, and the like. However, in SSI contexts, we need to work with tangible things - specifically: data that can be issued, stored, processed, transferred, requested and obtained. Still, in such contexts, we have observed that people use the term 'identity' to refer to various concepts/ideas, e.g.:

- a string of alphanumeric characters that can be used to identify someone, e.g. a name or an identification number (in general: an identifier),

- a (coherent) set of assertions (statements, claims) about someone, represented as data, e.g. digital, or in print, usually including an identifier of some kind;

- an artifact that contains such data, e.g. a passport, a (digitally signed) credential.

(Digital) identities, or personal data, are often associated with the ability to identify a person. Pfitzmann and Hansen, 2010, who tried to come up with a consolidated set of terms for identity and privacy, say that 'identity' is a subset of attribute values of a person which sufficiently identifies this person within any set of persons. The GDPR definition of personal data is "any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person ('data subject'); an identifiable natural person is one who can be identified, directly or indirectly, in particular by reference to an identifier such as a name, an identification number, location data, an online identifier or to one or more factors specific to the physical, physiological, genetic, mental, economic, cultural or social identity of that natural person".

Definitions such as these have various difficulties, perhaps the most prominent of which is that they do not provide a criterion that different people can use for determining whether or not something qualifies as an 'identity', and be in agreement on that. As a consequence, the relevance of having an identity, particularly in an SSI context, is not clear. Therefore, rather than searching for an answer to the question what an identity is, or should be, this pattern seeks to identify the concepts (ideas), relations between them, and constraints, that together form a coherent and consistent 'viewpoint', or 'way of thinking' about who or what an entity actually is. Readers that are interested in identification aspects are kindly referred to the identification pattern.

The figure below illustrates the concept of/idea that the being of a person, i.e. who the person is, is determined by everyone that has ideas, or knows about this person. This seems to be very much in line with the paradigm of identity as a network, as worked out by Kathleen Wallace: "The Network Self".

In our model, we postulate that identity is related to who or what an entity actually is, and that this is the combined perception (knowledge) of all parties that know about that entity's existence.

The figure has a person in its center (the 'protagonist' of the example) calls himself Piet van der Kluns, and perceives himself as being 28 years old, humorous and sporty. The other figures (a judge, a photographer, a colleague, and a mechanic) represent parties, each of which has its own view on the protagonist. The photographer finds him expressionless and dull, his colleague considers Piet to be reliable and helpful. They all have their own, subjective view on the protagonist, which can be expressed in terms of judgements and characteristics that they attribute to the protagonist. The number of parties that know about the protagonist will initially be very small, but will become larger over time. Also, the judgements and characteristics that parties attribute to the protagonist will develop and change over time.

It seems reasonable to say that the set of all judgements and characteristics that parties have attributed to the protagonist at some point in time represent who or what that protagonist actually is (at that time), and we might call that its identity.

However, this term has little practical relevance. First, the semantics of any attribution is (autonomously) decided by the attributing party, implying that attributes of different parties cannot be readily compared. The figure illustrates this by having the mechanic judge the protagonist to be unreliable, whereas the colleague finds him reliable. But even if parties agree, e.g. the photographer and mechanic both characterize the protagonist as a customer, but it does mean different things. While for a photographer, a customer is a person that it can instruct to sit down, perhaps do some make-up on, and take a picture of, this is not the case for a mechanic.

More importantly, in interactions between the protagonist and an arbitrary party, the latter will act, and make decisions using only its own, subjective knowledge. Any information about the protagonist that is used for that must therefore come from the part of the protagonist's identity that is also part of that party's knowledge. We will use the term partial identity of some entity as the knowledge that a specific party has about that entity. It implies that the identity of such an entity is the union of all of its partial identities.

This use of attributions is particularly relevant for SSI contexts in which the focus is on supporting (electronic) transactions. That support consists, amongst other things, of enabling a participating party to request for, and obtain data that are statements about entities (in particular about other participating parties) that this party determines to be valid for making the decision of whether or not to commit. Knowing the party that authored (issued) such data helps to determine not only the meaning of that data, but also to determine its (un)trustworthiness. Knowing that a set of data originates from a single partial identity is a prerequisite for doing this.

Formalized model

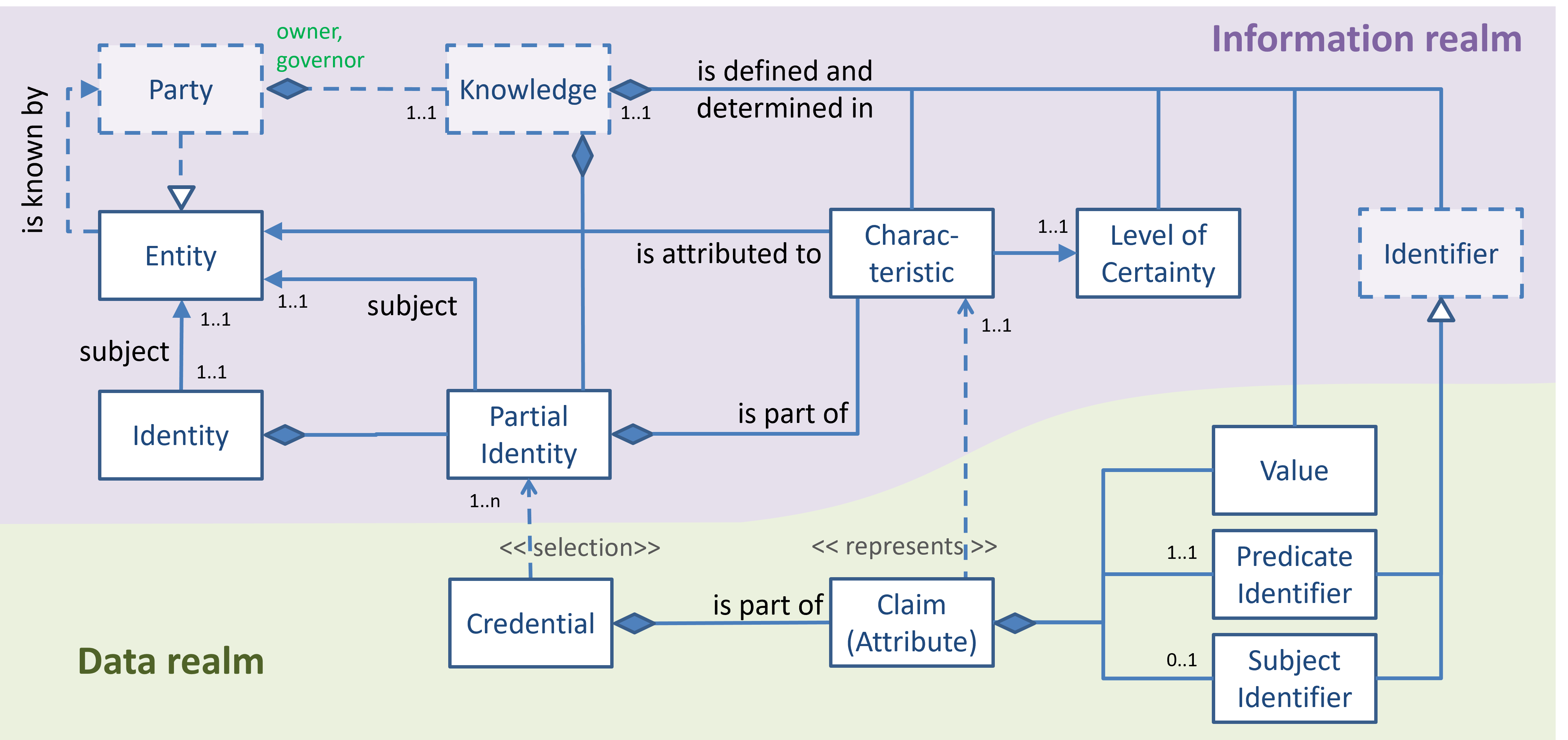

Here is a visual representation of this pattern, using the following notations and conventions:

The figure makes a strict distinction between (intangible) information concepts, which are presented in the purple area called 'information realm', and (tangible) data concepts, presented in the green 'data realm'. This enables us to link (tangible) data items that can be created, stored, processed, requested and obtained between (actors of) various parties with the (knowledge of) these parties, where actual decisions are being made. For details about parties, actors and actions and their relations, please refer to the party-actor-action pattern.

Identity - Information Realm

The figure expresses that an entity that is known to a party can be attributed characteristics, the precise nature of which is defined and determined in the knowledge of that party. The partial identity of which that entity is the subject, is comprised of every characteristic that the party has attributed to. We also hold that parties will associate each such attribution with a level of certainty, i.e. a measure of the strength of their belief that the attribution is correct. Such a level of certainty helps parties to determine whether or not the characteristic can be used for making certain decisions (i.e. is valid in arguments leading to such decisions).

Hence, the partial identity is part of the knowledge of that party, which implies that the party owns the partial identity, and governs it.

By saying that a party is also an entity, it follows that if it knows itself to exist, it can attribute characteristics to itself, and hence have a partial identity for which it is the subject.

For completeness sake, the figure shows that the identity of which the entity is the subject is comprised of all partial identities of which that entity is the subject, including the partial identity for which it is the subject. The figure thus (correctly) suggests that this term, while it can be properly defined, has no further relevance - at least not for our purposes.

The last item in the information realm is the identifier concept, which is better explained in the identification pattern.

Notice that the knowledge of a party defines (specifies, contains) whatever there is to know. This includes a specification of characteristics, the meaning and allowed values for the levels of certainty, the kinds of identifiers to use in various circumstances, etc. Also, this knowledge contains the set of (all) identifiers that the party has defined/created itself for identifying entities in various circumstances.

Finally, the knowledge of a party also holds the policies by which its actors determine which values and which (predicate and subject) identifiers to use for the creation of claims (attributes) and how to construct credentials from such attributes. While in general we would like to believe that an attribute that an agent of a party creates is a truthful representation of a characteristic in that party's knowledge (which is everything the party believes to be true), there is no guarantee for that. Parties may lie.

Identity - Data Realm

In the data realm, the figure also shows that a credential consists of various claims, each of which represents a (possibly complex) statement about an entity that is referred to as its subject. To this end, the claim consists of a subject identifier (which in practice may be implied - hence the 0..1 multiplicity), a(n identifier for the) predicate, which refers to the characteristic that is attributed to the subject, and 0..n values that provide the details of the characteristic. For example, if the characteristic is 'level of trustworthiness', there would be one value that represents the level of trustworthiness. If the characteristic is 'is over 18 years old', then no value is required. If the characteristic is 'children', the value may be a list of data objects, each of which would represent a person that allegedly is a child of the subject.

As said before, it is not self-evident that when a party creates attributes for some subject, such attributes actually reflect the characteristics that the party believes to be true for that subject. Parties may lie.

Sets of claims can be aggregated, meta data can be added to that (e.g. signatures and other proofs) to form credentials of various kinds. While ideally a credential would represent a subset of the partial identity of its subject, this can also not be guaranteed.

Digital signatures and other cryptographic proofs do not relate in any way to the truth of the information that the signed/proved data represents. However, they do serve other purposes. Under the assumption that there is no doubt that the private key that is used to digitally sign some data is under the exclusive control of a single party, the signature algorithm is secure and well-implemented, and the corresponding public key can reliably be dereferenced to that party, then that signature provides a proof of provenance of that data, as well a proof of immutability.